September 01, 2020 09:31 AM

Therapist development, or getting better at what you do, takes more than deliberate practice—it requires two things: 1) attaining systematic client feedback, sometimes called routine outcome monitoring (ROM) or feedback-informed treatment (FIT) via the Partners for Change Outcome Management System (PCOMS), and 2) taking your growth as a therapist to heart. Integrating these two critical aspects can open new vistas for those of you wishing to rapidly impact the quality of your work with clients. PCOMS helps us know we are on track, enables us to empower change, and provides an early-warning system for clients at risk for dropout or other negative outcomes. PCOMS also paves the way for your development as a therapist.

![]()

What the Research Says About Therapist Development

In contrast to the latest fads, there is a massive body of research about therapist development. A 20+ year, multinational study of over 11,000 therapists (Orlinsky & Rønnestad, 2005—read more about this study here) reports that two things are important: tracking your career development and articulating your current growth, i.e., the lessons you learn from your clients. Your view of your growth, both long-term and the here-and-now, impacts your ability to be vitally involved in the therapeutic process. This huge study asserted that if we don’t grow, we stagnate and burn out. Our best defense against burnout is our own professional growth.

2 Important Steps to Therapist Development

-

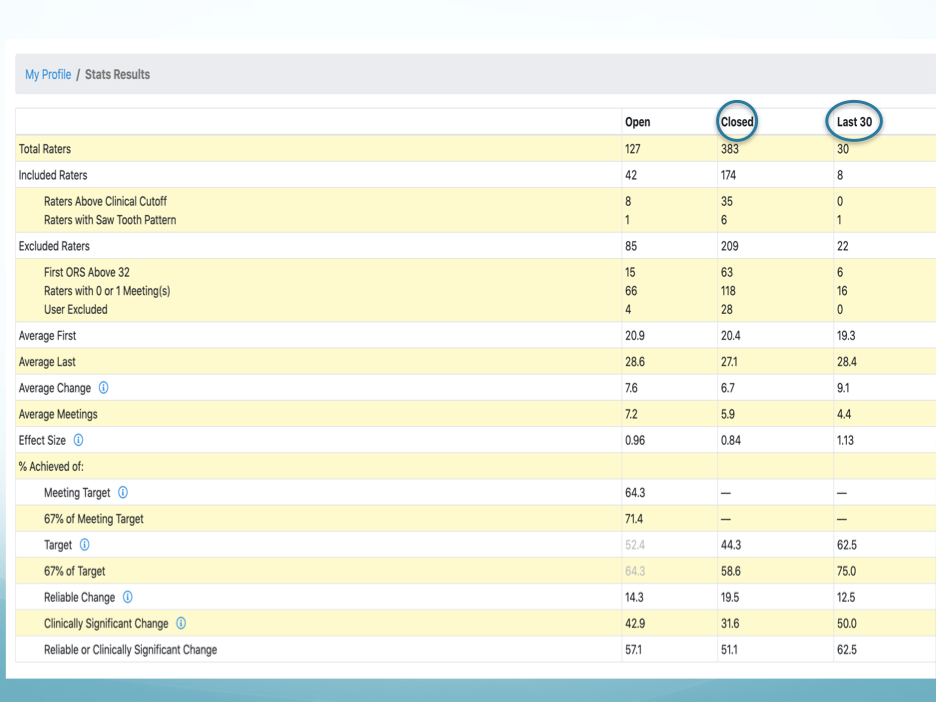

Track Your Career Development

The first step is to track your career development and take it on as a project. Look at your outcomes and definitively know whether you are getting better. Monitor your effectiveness in service of implementing strategies to improve your outcomes. Practice the skills of your craft (especially harvesting client resources and building strong alliances), learn new models, and monitor your results. Better Outcomes Now, the true web-based PCOMS app, provides an easy way to do this via an ongoing comparison of your last 30 closed clients to your total closed data set. Better Outcomes Now (BON) also allows you to evaluate time periods of your career so nothing is left to doubt or wishful thinking.

-

Articulate Your Current Growth

Second, pay close attention to your current growth. Take a step back, review your current clients, and consider the lessons you are learning. Empower yourself, like you would your clients, to enable the lessons to take hold and add meaning to your development as a therapist. Articulate how client lessons have changed you and your work and what it means to both your identity as a helper and how you describe what it is that you do.

Start with questions about clients who are progressing:

- What is working with these clients?

- What is client feedback telling you about progress and the alliance?

- How are you interacting with these clients in ways that are stimulating, catalyzing, or crystallizing change?

- What are these benefiting clients telling you that they like about your work?

- What are they telling you about what works?

- What does this mean about your identity as a therapist?

Clients who are not benefiting provide the best opportunities for accelerating therapist development and for encouraging you to do things you have never done and embrace the uncertainty endemic to the work as to life:

- What is working in the conversations about the lack of progress?

- What is client feedback telling you about progress and the alliance?

- How are you interacting with these clients in ways that open discussion of other options, including referral?

- What are these not-benefiting clients telling you that they like about how you are handling these tough talks?

- What are they telling you about what works in these discussions?

- What have you done differently with these not benefiting clients? How have you stepped out of your comfort zone and done something you have never done?

- What do these new things you are doing say about your identity as a therapist?

Tracking outcomes enables a big-picture view of therapist development from year to year and a microscopic view of daily lessons learned from clients. Both perspectives encourage you to continually grow, challenge assumptions, adjust to client preferences, and master new tools—to get better at what we do.

---

>> See firsthand how using PCOMS with BON aids in improving therapy outcomes and your development as a therapist. Request your FREE trial today:

.png)

.png)