March 26, 2024 05:45 PM

There have been great strides in behavioral health regarding diversity, equity, inclusion, and multicultural competence, but a need remains to translate these values into actionable practices in psychotherapy. While the case has been made that measurement-based care (MBC) is an evidenced-based intervention that improves outcomes and reduces dropouts, and recently, it provides a transparent collaborative process to engage clients in treatment, it has not been widely considered as a methodology for multicultural competence.

Of course, we are glad to see the field finally recognize the clinical and relational processes of MBC and get on board with its collaborative aspects. It’s been a long time coming. Collaborative clinical processes have been a part of PCOMS since its beginning (Duncan & Sparks, 2002). For example, Duncan and Reese (2015) suggest:

PCOMS is distinguished by its routine involvement of clients; client scores on the progress and alliance instruments are openly shared and discussed at each administration… With this transparency, the measures provide a mutually understood reference point for reasons for seeking service, progress, and engagement (p. 347).

Similarly, attention to individual experience, “amplifying client voice” and “socially just practice” (Duncan & Sparks, 2002, p. iii) have been part of PCOMS since the beginning, but more fully articulated in later publications. For example, Duncan (2012) asserts:

PCOMS seeks to level the psychotherapy process by inviting collaborative decision-making, honoring client diversity with multiple language availability, and valuing local cultural and contextual knowledge; PCOMS provides a mechanism for routine attention to multiculturalism and social justice. (pp. 98-99).

Valuing clients as credible sources of their own experiences, a central PCOMS value, is a necessary precursor to multicultural competence, enabling therapists to critically examine assumptions and practices and allow clients to teach clinicians how to be most effective with them. This potential of PCOMS to promote cultural humility and multicultural competence has been recognized in graduate training, in both marriage and family (Sparks et al., 2011) and counseling psychology programs.

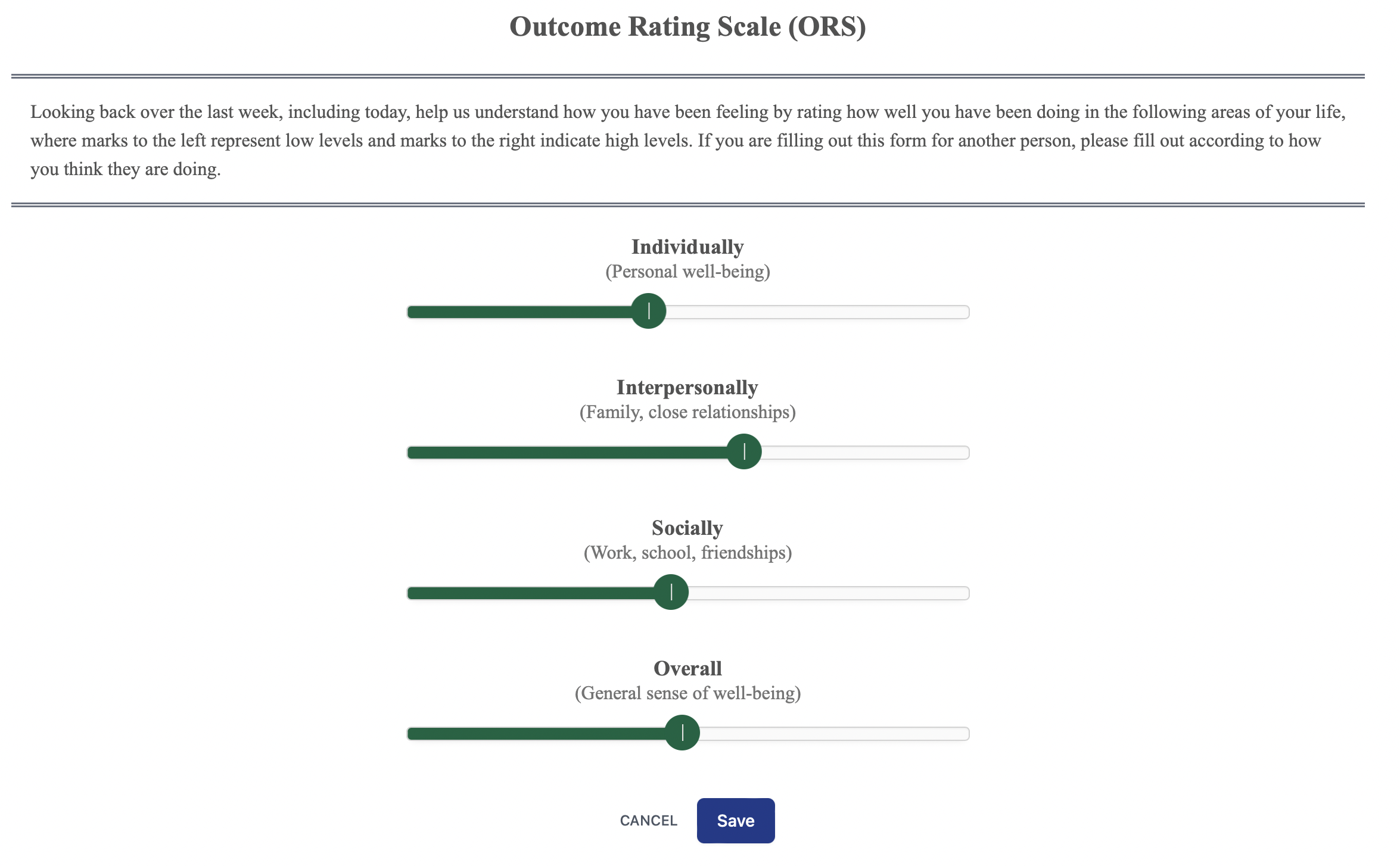

The Outcome Rating Scale (ORS)

Beyond ensuring representative diversity and educating dominant culture practitioners about privilege and other biases, less has been proposed about doing culturally responsive work with this client with this therapist. PCOMS provides a way to address client experiences of marginalization and discrimination as well as differences between client and therapist.

Inquiring about and honoring client perspectives of outcome starts with a shared understanding of the purpose of therapy. Clients rate themselves resulting in a score that only they can interpret. The therapist provides reference points (clinical cutoff, expected treatment response [ETR]) gleaned from normative data to understand the client’s score and validate their experience (e.g., “People who score this low tend to be having a rough time of it, is that right?” Or “You scored like people who are looking for a change, is that right?”), but the client is the final arbiter of meaning.

The content-free dimensions of the ORS allow clients to describe the meaning of their scores without preconceived theory, symptom, or therapist-derived constraints. Thus, client accounts retain the richness of real life, including the unique back-stories that contextualize their dilemmas, including the possibility of oppression and discrimination.

Conversations generated by client scores on the ORS are openings for therapists to inquire about clients’ reasons for service, views on precipitating and contextual factors, the impact of the problem in clients’ lives, and thoughts about general directions for problem resolution. The ORS contextualizes presenting problems beyond diagnostic categories, running counter to practices that pathologize clients of color and other historically marginalized groups at higher rates.

Putting client reasons for service in context also promotes consciousness-raising for both client and therapist, helping to identify forms of oppression and marginalization that may contribute to distress. Consequently, the Outcome Rating Scale creates opportunities for cultural humility and responsiveness. It provides a logical place for such conversations to occur if they do not do so naturally during treatment, enabling the space to make humble attempts at getting closer to the client’s unique experience.

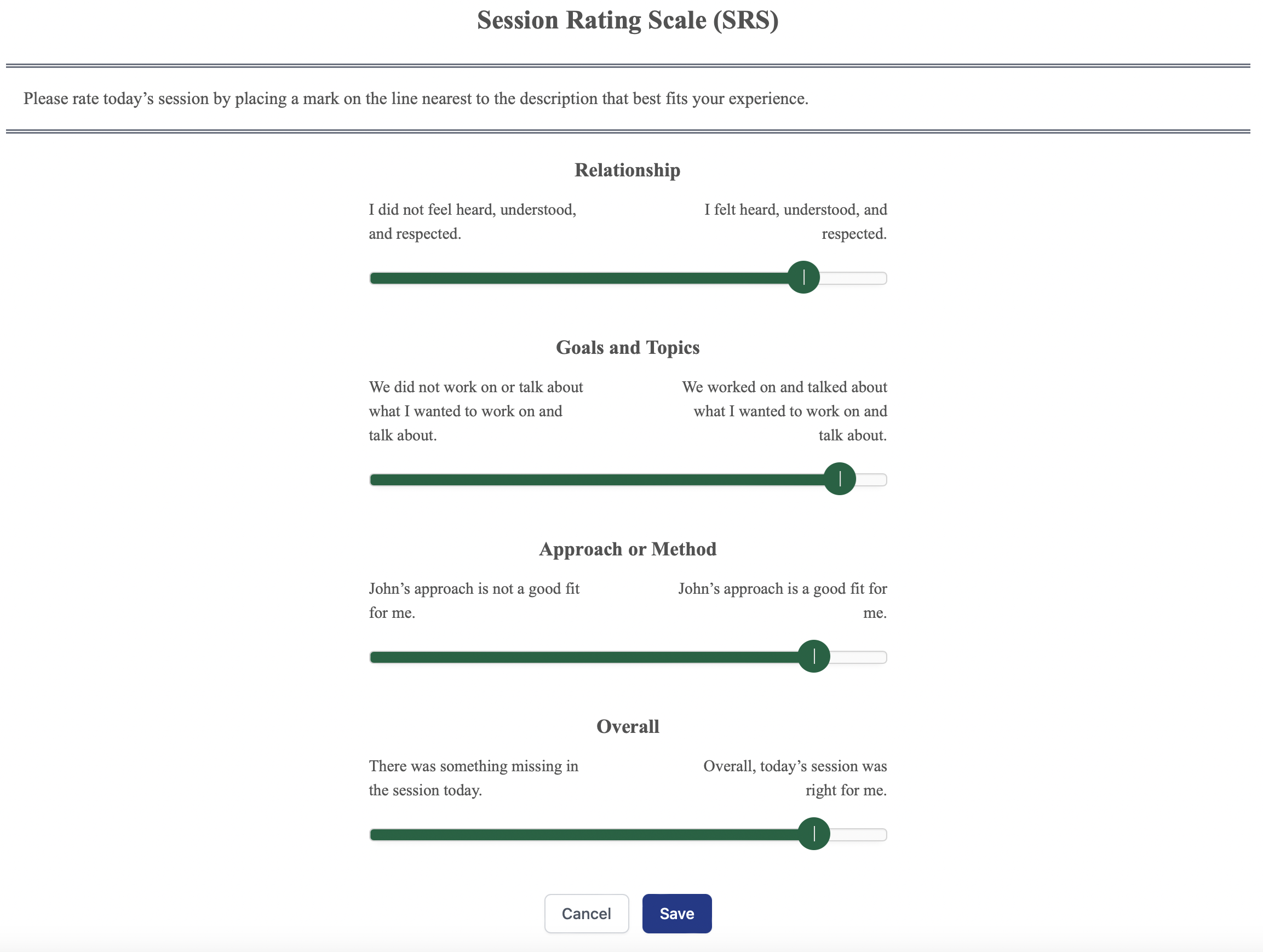

The Session Rating Scale (SRS)

The use of the SRS continues the value of client privilege and opens space for the client’s voice about the alliance and therapist/client fit, specifically aiming to identify alliance ruptures before they negatively impact outcome. The SRS provides a structure to address the alliance, allows an opportunity to fix any problems, and demonstrates that the therapist is committed to forming good relationships. The SRS also encourages ethnic/cultural/racial/orientation differences to be transparently and routinely discussed; it provides a mechanism to initiate conversations that might be more difficult for therapists to broach without a structure in place.

Finally, the SRS empowers therapists to elicit and embrace feedback and therefore may enhance therapist ability to host conversations about therapist-client differences. By routinizing the asking for and receiving client feedback about their experience of therapy, the SRS promotes openness to client perspectives, laying the foundation for cultural humility and responsiveness. However, it requires therapists to embrace that they can never fully understand a client’s cultural experience, with only continued efforts to gain a closer approximation.

When clients are not benefitting, the SRS provides an opportunity to entertain how culture, including therapist and client differences, are contributing factors to the lack of success. Like the ORS provides a platform for understanding the client’s experience, discussing client benefit, and collaboratively altering therapy, the SRS enables a structure for conversations about the relationship and alliance—to demonstrate a sincere curiosity and desire to understand the client’s experience, including how their social locations may be salient.

For example, with any scale lower than 9 cm or any scale lower than the rest, the therapist might say after noting a lack of change:

Given our (ethnic, racial, gender, orientation, or cultural) differences, I was wondering if you thought it might be helpful to discuss and if I needed to make adjustments because of those differences. I would greatly appreciate your help in understanding these things because coming from a different ( could include “privileged” if applicable) culture, I am certain that I have inevitable blind spots and biases that I am unaware of.

A sincere curiosity and desire to understand the client’s experience, especially those whose experiences are far different than your own, are critical. Humility about such differences and a desire to be helpful will usually win the day. There is no such thing as an expert in the diversity of the human condition, only humble attempts at getting closer to the client’s unique experience.

Graceful acceptance of any problems and a willingness to be flexible speak reams to the client and usually turn things around. Punctuating this point is the finding that clients who report alliance problems are twice as likely to achieve a successful outcome. Negative scores on the SRS, therefore, are good news and should be celebrated. Practitioners who elicit negative feedback tend to be those with the best effectiveness rates.

Multicultural competence takes a sustained effort to include clients and embrace their feedback—to not reduce psychotherapy to the medical model equation of diagnosis plus prescriptive treatment equals cure, nor clients to cultural, ethnic, racial, or gender stereotypes or pharmaceutical-sponsored checklists, nor the proclivities of enlightened psychotherapists who know better than clients what they need. The ORS and SRS help this effort.

The Evolution of Feedback: Toward a Multicultural Orientation

An article (Duncan & Reese, 2024) addressing this aspect of PCOMS will soon appear in the journal, Psychotherapy. Here is the abstract:

There have been great strides in psychology regarding diversity, equity, inclusion, and multicultural competence, but a need remains to translate these values into actionable practices in psychotherapy. While the case has been made that measurement-based care is an evidenced-based intervention that improves outcomes and reduces dropouts (de Jong et al., 2021), and recently, that it provides a transparent collaborative process to engage clients in treatment (Boswell et al., 2023), it has not been widely considered as a methodology for multicultural competence. We trace the evolution of what was once called “patient-focused research” (Lambert, 2001) and identify a significant change in recent writings to include important clinical and collaborative processes, a transition from a strictly normative or nomothetic understanding of the value of feedback to an appreciation of its communicative or idiographic processes. We propose that systematic client feedback promotes a “multicultural orientation” (Owen, 2013) at the individual therapist-client level, that client responses to outcome and process measures can foster cultural humility and create cultural opportunities (Hook et al., 2017) to address marginalization and other sociocultural factors relevant to treatment. Using one system to illustrate what is possible for all feedback approaches, we present client examples that demonstrate an integration of a multicultural orientation. We suggest that systematic client feedback can provide a structure to address diversity, marginalization, and privilege in psychotherapy.

Email Barry at barrylduncan@comcast.net for a pre-pub copy.

.png)

.png)